The World’s Best Restaurants

Why The World’s 50 Best Restaurants 2019 List Is More Controversial Than Ever

Even now, five years on, René Redzepi’s face still lights up when he recalls the April night his restaurant Noma was named best restaurant in the world for the fourth time. After a difficult 2013, whose nadir came when the Copenhagen restaurant dropped one position on the World’s 50 Best Restaurants list, reclaiming the title the following year felt like redemption. “We had been wondering is this it? Is it the beginning of the end?” Redzepi, 41, said with a smile as he surveyed the crowd at a recent outdoor party in Copenhagen’s meatpacking district. “ So when we won, it was like “Oh, you still like us.” It was even better than the first time.”

On June 25, when the 18th edition of the World’s 50 Best Restaurants’ lavish award ceremony takes place in Singapore, he may well get the chance to repeat the sensation. After closing the original Noma in 2016 and re-opening it in 2018 in a new location and with a new menu tied more closely to the seasons, Redzepi and his team are again among the favorites to cinch first place on the prestigious list. But as of this year, no other chefs — at least apart from any who have also rebuilt their restaurants from the ground up — will have the same opportunity. In January, the organizers of World’s 50 Best announced that any restaurant that takes or has previously taken the top spot on the list is disqualified from subsequent editions and moved instead to a Hall of Fame-like collection called The Best of the Best. That includes 2018’s #1, Osteria Francescana, as well as five other revered restaurants.

It might seem a small matter, but coupled with other recent changes, the new rule — which came as a shock to many in the restaurant industry — reveals a tremendous amount about the relationship between chefs and an institution that for nearly two decades has played an outsized role in determining which restaurants receive the lion’s share of bookings, accolades, and media attention. And it raises a question that only a few years ago would have been unthinkable: in this age of social media, can any conventional system for evaluating restaurants, including World’s 50 Best, remain relevant?

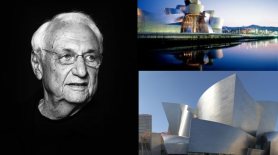

Italian chef Massimo Bottura talks with the press after receiving the Best Restaurant award for his restaurant L´Osteria Francescana during the World’s 50 Best Restaurants awards in Bilbao on June 19, 2018. Ander Gillenea— AFP/Getty Images

Launched in 2002 by editors at the U.K.-based Restaurant magazine, the World’s 50 Best Restaurants ranking quickly became one of the most influential forces in modern gastronomy. A restaurant that earns a spot on the list routinely sees a bump in reservations, and those that make the top 10 can expect a bombardment from eager diners and media alike. “Within 24 hours of the ceremony, we got 2 million booking requests,” says Catalan chef Joan Roca, whose restaurant El Celler de Can Roca, took number one in 2013 and 2015. “We’re still feeling the impact.”

Beyod the publicity frenzy, the list also gained influence by tapping into the very human need for approval and belonging. Unlike the Michelin Guide, which is judged by a small group of anonymous inspectors, the 50 Best ranking is today decided by more than a thousand mostly well-known chefs, food writers, and gourmands — a composition that gratifies chefs whose restaurants make the list with the knowledge they have the respect of their peers. “To know that the people you so admire return the affection is a beautiful feeling,” explains Roca.

Yet for all its success, the ranking has always been plagued by controversy. There is no prohibition against lobbying, nor are voters required to pay for their meals, so some countries’ tourist boards — and even some individual restaurants — have subsidized expensive junkets to bring jurors to their tables. The list has also had difficulties achieving regional and gender diversity. Only 16 — a historic high — of the restaurants on 2018’s list are located outside of Europe or the United States. Five of them (also a record high) are led by women, although three of the women (at Arzak in San Sebastian, Cosme in New York, and Central in Lima) share their restaurant’s head position with a man, and another (at Nahm in Bangkok) assumed the role from its former male head chef too late in the year to have been considered.

More controversial, however, is the decision to remove previous number #1s from subsequent competitions. The organization presented the move as part of its efforts to diversify the list’s upper echelons. “There was some stagnation in the top 10,” says Pietrini. “We don’t want to artificially skew it, but we think it’s a healthy decision to make sure we’ve got a new dynamic every year.”

Yet although World’s 50 Best decided to create The Best of the Best itself, TIME reporting found that the rule change to withdraw winning restaurants from subsequent competition did not come from the organization itself. It was actually proposed — some would say imposed — by half a dozen or so highly ranked chefs, some of them former #1s, some of them close to the top..

Massimo Bottura, whose Modena restaurant Osteria Francescana took the top slot in 2016 and regained it last year, was one of them. “In the last several years it’s been us, the Rocas, and René Redzepi as at least two of the three best restaurants in the world,” he says of their motives. “I think it’s time for others to be there, especially from the younger generation.”

Bottura says he first heard of the idea years ago from Gaston Acurio, whose Lima restaurant Astrid y Gaston is currently #39 on the list. “When I accepted the award [in 2013] for best restaurant in Latin America, I said to the audience that I hoped to see someone new in my place the following year,” Acurio says, adding that he later mentioned the idea to the organization’s administration. “I believe the 50 Best shouldn’t be a tool for competition but a union that promotes excellence, diversity, and talent.”

But according to a source with knowledge of the process who asked for anonymity because he did not have permission to speak publicly on the subject, the core group that began pressing in earnest for the change last year was driven not only or even primarily by an attempt to unclog the top, but also by an effort to avoid the decline in reputation that some notable chefs have suffered once they fell from first place. Daniel Humm, whose restaurant Eleven Madison Park in New York won the top spot in 2017, acknowledges the impact of a drop was a factor in the group’s proposal. “We’ve seen restaurants fall down the list even though they were getting better and better,” he says. ”There have been a few chefs in the past who started to feel more pissed off and mistreated, and they started to not show up [to the ceremony], and that was hurting the whole thing, because the spirit of 50 Best is community.”

For a handful of chefs to upend the rules of the game in order to avoid the perception of diminishment gives a sense of just how influential the ranking has become. Some highly-regarded chefs tell TIME they have experienced depression for failing to make the list, while others, like Christopher Kostow of Napa Valley’s Meadowood, have lambasted it for skewing toward the new and “hot” rather than rewarding the kind of excellence that comes only with years of practicing a craft. “It’s an assassin list,” agrees Ferran Adrià, whose restaurant elBulli held the title five times before it closed in 2011. He, like Redzepi, only learned of the new rule once it was publicly announced. “Once you fall, you disappear not only from the list, but from the [industry’s] whole little world.”

Yet, by removing winners from subsequent consideration, the new rule may well undermine 50 Best’s own influence. In the past, the sustained presence of a restaurant like elBulli or Noma in the top slot helped turn their respective countries into gastronomic powerhouses. “If a chef in Seoul won four times in a row, Korea would become an international culinary destination,” says Adrià. “If she wins only once, it’s nice for her, but it won’t have the same effect.”

And of course, the ranking itself runs the risk of losing credibility since it no longer represents all of the best restaurants. “That’s exactly the kind of question we asked ourselves,” Pietrini admits of the administration’s deliberations. “It was not a quick decision. I know there are rumors that we were pressured into it. I will only say that at the end of the day, the decision was ours alone. And we would not have made that decision without a long-term plan.”

As part of that long-term plan, the organization appears to recognize that its future may not lie with the ranking. Later this year, it will launch a global database, called 50 Best Discovery, that tracks restaurants that garnered votes but not enough to make the ranking, and will also include bars from its sister list. “We want to take 50 Best from a listmaker to a media platform, and as I like to say internally, a progressive force,” she says. “Our objective is not to be more influential.”

Of course, they may not have much choice in the matter. Other awards, rankings, and guidebooks have emerged in recent years, and although none has yet attained the prominence of 50 Best, they have eroded the perception of the list as the newest, most plugged-in kid on the block.

And the impact on bookings and attention that 50 Best enjoyed now been far surpassed by the wildly influential Netflix show Chef’s Table. Ana Ros, of Slovenia’s Hisa Franko, goes so far as to say the show, on which she appeared in 2016, saved her business. “We went from having empty tables several months of the year to having a permanent waitlist,” she says. “Although we assume being on the list has had an impact (Hisa Franko entered the top 50 last year, at #48), we don’t know for sure. It hasn’t been as noticeable”.

Even more challenging has been the rise of social media; to a significant degree, millennials make their decisions about where to eat based on what they see on Instagram, rather than on conventional reviews or rankings. That’s part of the reason why, after nearly a century of independence, the storied Michelin guide, which saw its own influence wane with the rise of World’s 50 Best, now accepts commissions from countries or regions eager for its coverage; Austria, for example, recently paid 600,000 euros to revive its defunct red guide.

One test of World’s 50 Best’s continued relevance at this year’s ceremony in Singapore will have less to do with who steps onto the stage to receive its top award than with who is applauding from the audience. In the past, the ceremony drew nearly every name on the list, along with dozens of other chefs who came for the party and the chance to see friends from all over the world. But increasingly, even chefs who have been recognized by it — like Christian Puglisi of Copenhagen’s Relæ, who won the organization’s sustainable restaurant award in 2015 and 2016 (#56 on this year’s list) and Dominique Crenn, who in 2016 won the organization’s controversial Best Female Chef award — are speaking out against the kind of publicity, networking, and deep pockets that the list is perceived as rewarding. And this year, some heavy hitters, including Grant Achatz of Alinea (#34 in 2018) and — even though Noma is a contender for #1 — Redzepi won’t be there.

Redzepi is staying home because the ceremony conflicts with the opening of a new menu at Noma. But he is also opposed to the rule change, and wonders if it will ultimately reduce World’s 50 Best’s influence. “If a chef manages to create a restaurant that defines the zeitgeist for more than one year, shouldn’t the list reflect that?” he asks. That criticism is shared by Ros in Slovenia, even though her restaurant stands to benefit from the change. “I think it’s a faux pax that may hurt them,” she says. “I’m an ex-athlete, so I don’t understand how you can tell someone they can’t compete.”

As a former professional cyclist himself, Daniel Humm understands the sentiment. Although he says that he is “at total peace” with the fact that Eleven Madison Park is no longer eligible for the list, he’ll be attending the Singapore ceremony with mixed feelings. “I’ve got competition in my blood, so I’ve always liked going into that room,” he says of the hall where the world’s best chefs gather to learn of their ranking. “It’s like in basketball when it goes down to buzzer and there’s a guy taking a three point shot. I always want to be the guy with the ball.”